For those of us who work in public higher education there’s something that we need to always keep in mind. Our students are better than we think they are. That isn’t to say they don’t need the services we provide of course, but that we tend to underestimate them or act on our own bias about them directly but instituting structures that prevent them from achieving what they can.

I think this is particularly the case with much of what we are trying to implement with reform initiatives that come from the private sector, especially the reforms that the Gates Foundation is pushing forward, such as the idea that college education needs to lead to a career. It sounds reasonable of course, but it’s also quite limiting, especially when you consider that for most children in high school who come from a home where no one has been to college the idea of a career isn’t as much abstract as it is alien. I still remember when the child of a neighbor came to my CUNY campus for a Boy Scout event and he was convinced that I had to be a janitor because in his experience if you worked in a school you were either a teacher, a security guard or a janitor. Nothing else made sense to him. He ended up in prison. For him a career was not an idea he could even wrap his head around.

Education shouldn’t be about outcomes. Yes, that sounds radical on some level, but you don’t go to college to get a bunch of skills you can check off. That might be some of what you do, but mostly you go to engage yourself with people, ideas and situations that are beyond your current capacity. You go to college to not do anything particularly useful and the things you learn aren’t really useful at all until they absolutely are at the time you need them. They aren’t quantified or qualified. They are experienced and embodied. You create, as Bourdieu would say, a person with a durable habitus.

When CUNY was started in 1847 as the Free Academy the big debate was why should the sons of shopkeepers, tradesmen, and even worse, unwashed immigrants, spend any time on the liberal arts when they could be simply educated in the practical arts. That was all they needed. Only the gentlemen needed to be educated like gentlemen. The “practical” people lost that debate in 1847 but it never goes away. It comes back regularly, usually put forward by the rich, the powerful and the people who send their own children to Waldorf schools and expensive liberal arts colleges.

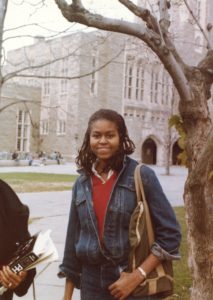

The young Michelle LaVaughn Robinson was a working class kid whose father was, to put it less politely than we hear more often than not, worked in a plant that dealt with the effluent of sewers, or better said, shit. Her mother was a homemaker. Her ancestors were kidnapped, enslaved and driven out of the South by Jim Crow and all that went along with that. In a world of outcomes and careers what would a typical reformer do but put her into some nice program that would lead to perhaps being less than we know her to be now. Still, she went to Princeton.

She didn’t go to Princeton to have a “career.” She went to Princeton to become a powerful, confident, fully formed human being. That’s a liberal arts education.

I often think that when the British Army had their back against the sea at Dunkirk their officers looked into the turbulent waters of the English Channel and remembered their old, worn schoolbooks in dead languages and the cry of joy of the Ten Thousand when they reached the shore in Xenophon’s Anabasis. Thálatta! The sea! They would not be defeated. Back at Downing Street, at the docks of Dover and in the halls of Parliament the sea became not a barrier, but salvation. Those who struggled with the ancient texts in hoary cold classrooms didn’t learn how to conjugate verbs or pronounce dead words. They learned how to react to something that a small child couldn’t imagine or foresee.

That’s education.